Mrjoshua

Member

Username: Mrjoshua

Post Number: 839

Registered: 03-2005

Posted From: 68.42.76.160

| | Posted on Saturday, May 27, 2006 - 12:48 pm: |    |

Creative Destruction

When cities burn, they rise from the ashes. And then there is Detroit

By JULIA VITULLO-MARTIN

May 27, 2006; Page P9

The Wall Street Journal

Seven Fires

By Peter Charles Hoffer

PublicAffairs, 460 pages, $27.50

When a pre-dawn fire raged through a 21-acre site on the Brooklyn waterfront earlier this month, destroying 15 industrial buildings built in the 19th century, New Yorkers could speak of little else -- and no wonder. The nine-alarm blaze was New York's largest fire in 10 years, other than the World Trade Center inferno of 9/11, and it was almost certainly not an accident. Fire marshals found that accelerant had been poured in five separate areas, making clear that this was a professional job.

How to make sense of such wanton destruction? Peter Charles Hoffer's "Seven Fires" gives some clues. In search of "the urban infernos that changed America," as his subtitle has it, Mr. Hoffer ranges from the Boston fires of 1760 to the World Trade Center attack of 2001, stopping along the way in Pittsburgh (1845), Chicago (1871), Baltimore (1904), Detroit (1967) and Oakland Hills, Calif. (1991). He notes the shockingly destructive force of urban fires and, over time, the triumphs of various fire-prevention measures, such as building codes and open-space planning. He is at his best when talking about the nature of fire itself -- how it takes on a life of its own. Though fire lacks the essential human capacity for intent, Mr. Hoffer notes, "no one who has gotten close to a serious fire mistakes its will to master its surroundings."

Mr. Hoffer is at his worst, however, on human motivation. His chapter on the infamous Detroit fires that destroyed hundreds of buildings during five days of race riots in July 1967 is titled suggestively: "Motown, If You Don't Come Around, We Are Going to Burn You Down." And yet he spends a lot of time excusing the rioters. "Angry people cannot contain their frustration and alienation forever," Mr. Hoffer writes. He distinguishes looting, which "had its rationale," from the setting of fires, since "fire does not transfer wealth or redistribute goods." Just proposing such distinctions has the effect of legitimating anarchy and violence -- or of trying hard to do so.

But even Mr. Hoffer cannot sustain the effort. He notes that, while arson was the most frequent crime committed by slaves against their masters in the antebellum South, Detroit's arsonists in 1967 were not slaves -- no matter how powerless they thought themselves to be. At one point Mr. Hoffer argues that the arsonists were merely young vandals rebelling against their parents. In a non sequitur that at least approaches the truth, he concludes that fire in 1967 Detroit "had become one tool of political incendiaries, unthinking native terrorists."

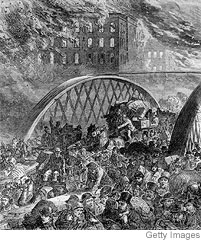

Panicked crowds flee the Chicago Fire of 1871, crossing the Randolph Street Bridge

What makes Detroit's fires unique, as Mr. Hoffer acknowledges, is that they destroyed neighborhoods that stayed destroyed. The Chicago fire encouraged the development of new construction methods. Before long, skyscrapers rose out of the city's ashes, and its economy roared into the 20th century. After Baltimore's fire, the city expanded its port and transformed what had been a fairly ordinary downtown. But Detroit has had no rebirth. The flames of the 1960s seemed to have seared its soul.

As for the World Trade Center, the story is reasonably clear -- a surprise attack, the bravery of New York's firefighters and "mortal flaws" in the structural design of the buildings. The Port Authority (the original owners of the Twin Towers) had taken advantage of its exemption from the city's stringent codes to construct bigger and cheaper buildings than would have otherwise been allowed. Fatally, it created vast, out-of-code, rentable floors supported by lightweight trusses bolted to external panels. When the trusses melted, everything else gave way.

For all sorts of reasons -- mostly technological -- fire does not seem to threaten cities as it once did. But crime and catastrophe (including earthquakes) can always set urban neighborhoods alight. As buildings all over the country grow ever taller and more massive, it is useful to be reminded of this incendiary reality. "Seven Fires" is a compelling read.

-----------------------------

Ms. Vitullo-Martin is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. |

Mackinaw

Member

Username: Mackinaw

Post Number: 1602

Registered: 02-2005

Posted From: 68.248.4.60

| | Posted on Tuesday, May 30, 2006 - 12:59 pm: |    |

bump

Well, this looks like an interesting read, but mainly I am eager to see how this author puts a race riot in the same category as other catastrophic fires. It would seem that our early 19th century fire, which came right before we boomed, should be the subject of such a book, but I wonder why the author chose the race riot.

I notice that the WSJ headline borrowed from the Detroit motto. |

Barnesfoto

Member

Username: Barnesfoto

Post Number: 2028

Registered: 10-2003

Posted From: 66.2.148.171

| | Posted on Tuesday, May 30, 2006 - 5:35 pm: |    |

I would hope that Mr. Hoffer devotes at least one chapter to the widely popular sport of arson for profit masked as random arson. Much of the burning of Detroit, as well as the South Bronx, can be attributed to this particular shade of destruction. |

|